In the Spring of 1993 I looked at my four year old son and thought, "He's going to be getting all of his information and entertainment from digital media."

There was just one problem with this realization, I had no idea what digital media was.

Yes, I like so many had a new Mac classic II. But it was, for me, little more than a typewriter with an attached filing cabinet, with some great editing features.

I had though, a vague vision of what I had in mind. I had written it on a cocktail napkin the evening before while drinking a good single malt at a pleasant local. The vision was based on what I had been doing for the past two years.

I had saved the first automotive magazine style TV show on the Discovery channel by producing, and financing, four shows from Europe. I say shows, rather than the seven minute segments they aired as, out of respect for the arrangements they took, the miles traveled and the amount of footage shot. I had done it all on a bet. I had spent the last several years in the Italian Motorcycle industry, and had remarked to one of the show's segment producers that the Discovery show needed some real automotive stories of depth and character. Implying this would be a good way to attract a solid viewership and some good automotive industry sponsors. Thus the bet made at the Long Beach GP. Six months later I had a crew in Europe to shoot shows on BMW Motorsport and the M5 cars, the first visit to the new Bugatti factory in Campogalliano and first test drive, Peter Kaus's Rosso Blanco Museum, and the amazing designer Franco Sbarro at his school in Grandson Switzerland, outside Geneva.,

From there I produced arguably the first personality driven automotive show, with Tim Allen, training for and racing in the Long Beach GP Celebrity race for NBC.

From there I had raised the capitol, 75K, for the pilot of a new show. This I chose to do on the relationship between the Italian high performance manufactures and the Carrozzeria. Hell it was a way to get back to Italy and visit Bertone, ItalDesign, Pininfarina, Zagato, Alfa, Ferrari and Lamborghini, and see if they wanted to let me screw up production for a day or two while we filmed. They did.

This then became part of a bigger series in development with Time Warner, with a 350k budget and broadcast guarantee. Now, you'll notice the all important phrase there, 'in development'. Let's just say 'in development' can be an interminable purgatory in TV production. This was not to prove too interminable, as our budget had been reallocated, as did many a production budget 'in development', to develop the hardware and software of the first interactive TV system for TW's Orlando network.

But while we had been in development, Michael Israel, who was TW's creative director, and I had spent some time in TW's newly established digital lab. He was showing me how they were taking videos of comedy stage acts onto this new platform called CD-ROM. Now the problem, as I saw it, was that computer OS hated 29.9 frame per second interlaced video. It seemed to follow the audio track, dropping frames at will to keep up. Kind of like the Jack Benny radio hour with bad visuals.

It was later that evening, over the aforementioned scotch that I had an idea. I was growing weary of the short Cliff's Notes scripting and production of automotive TV. Wouldn't it be interesting to use this new medium to blend the depth of a print publication, with the film, animation and audio of broadcast?

Fortunately this concept, and the inspiration, or perhaps, future vision justification of Miles' getting his info from digital media, came three days before we found out our budget for the new car show was going to Orlando without us.

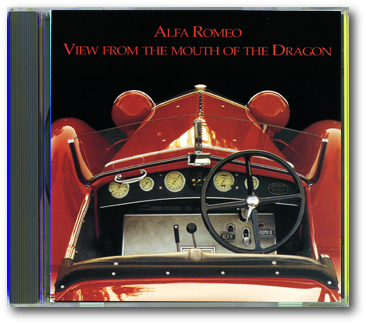

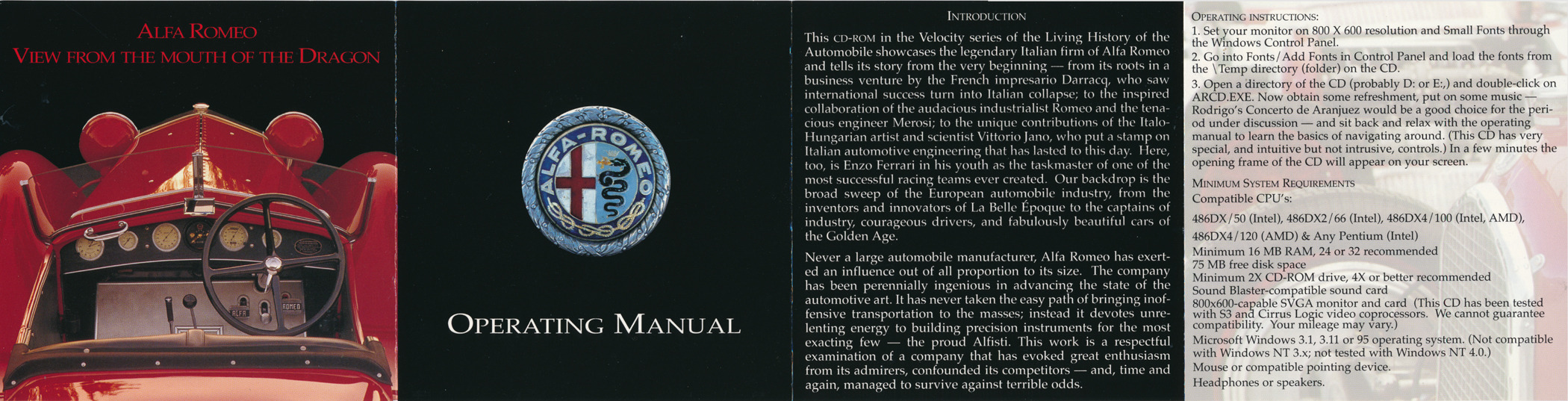

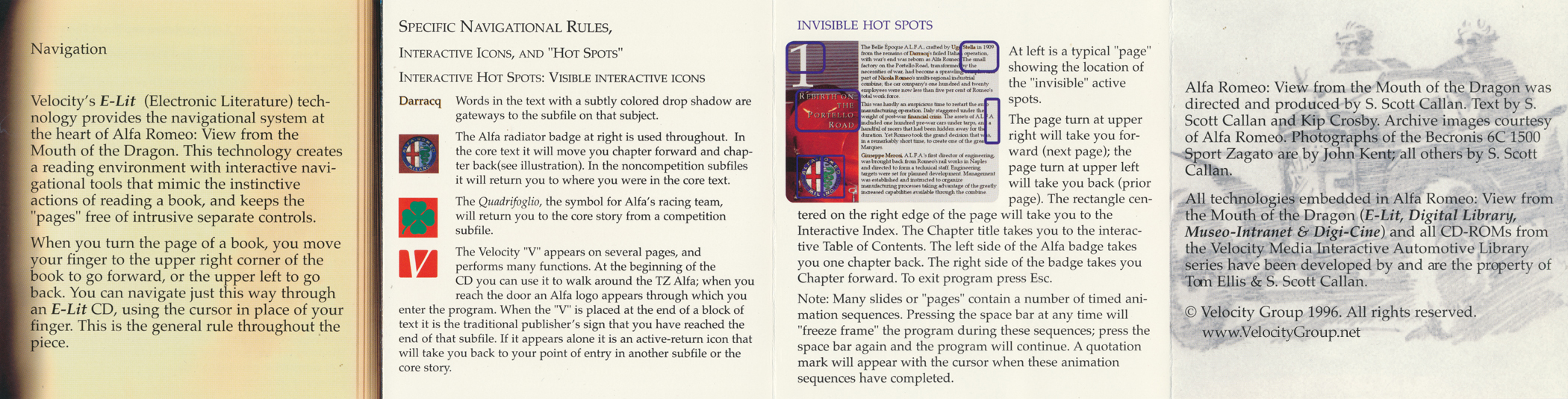

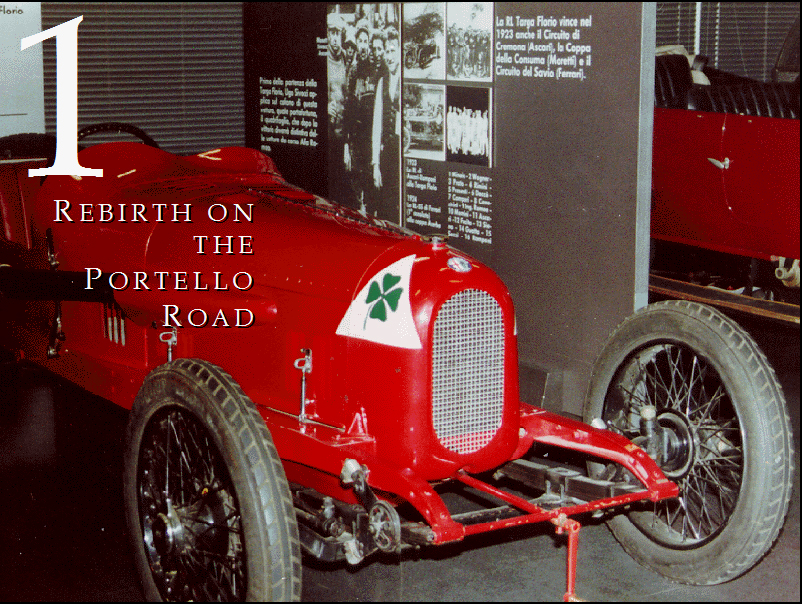

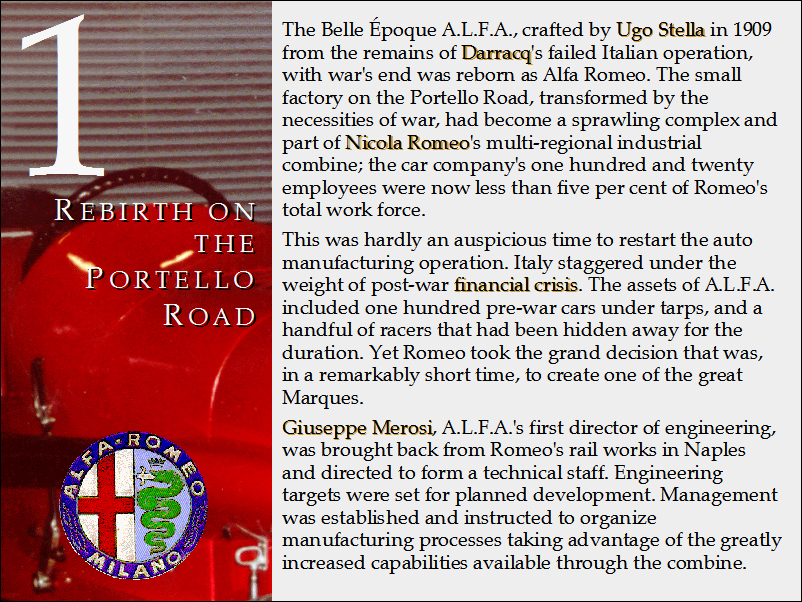

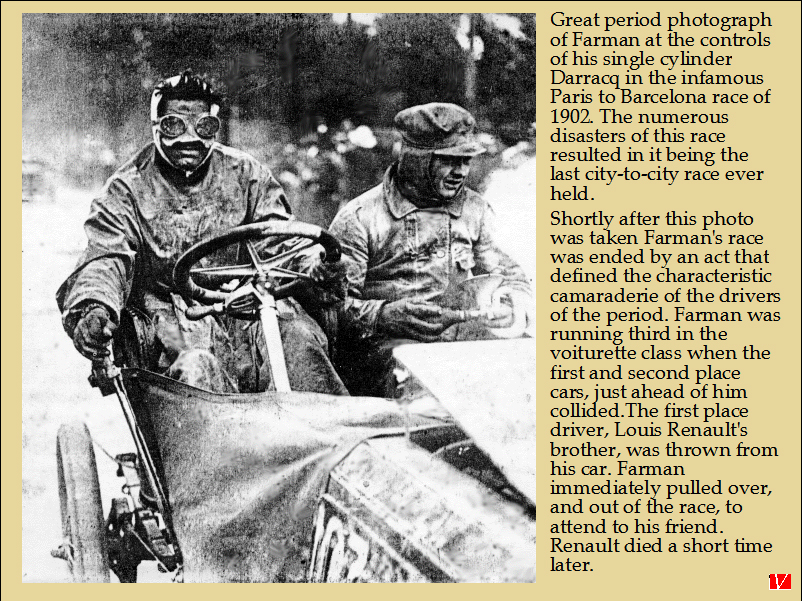

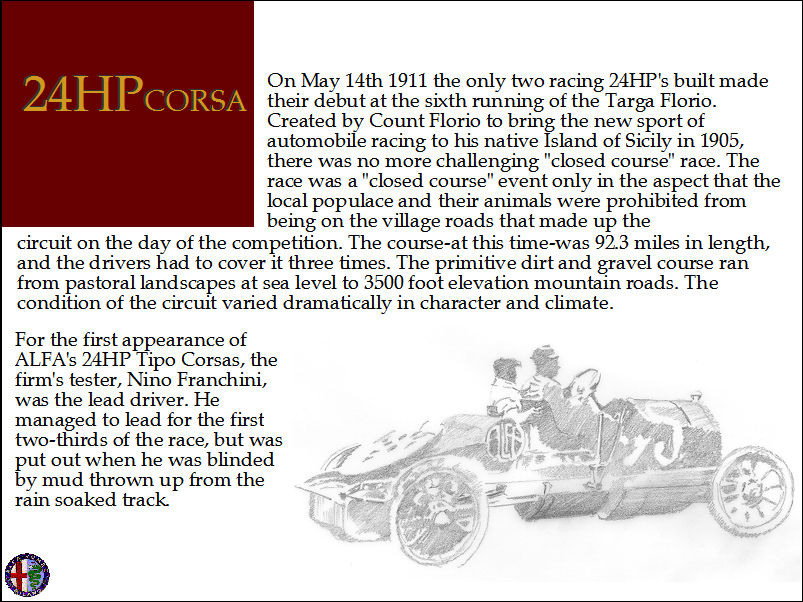

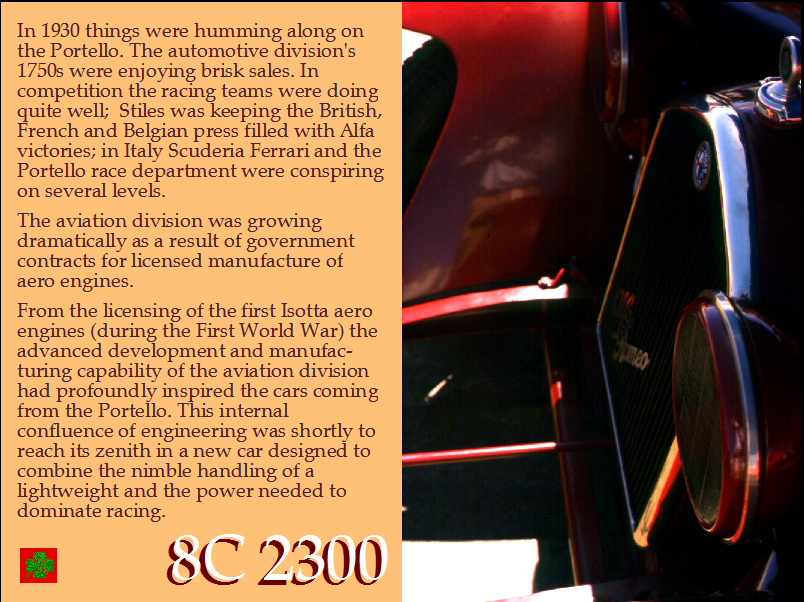

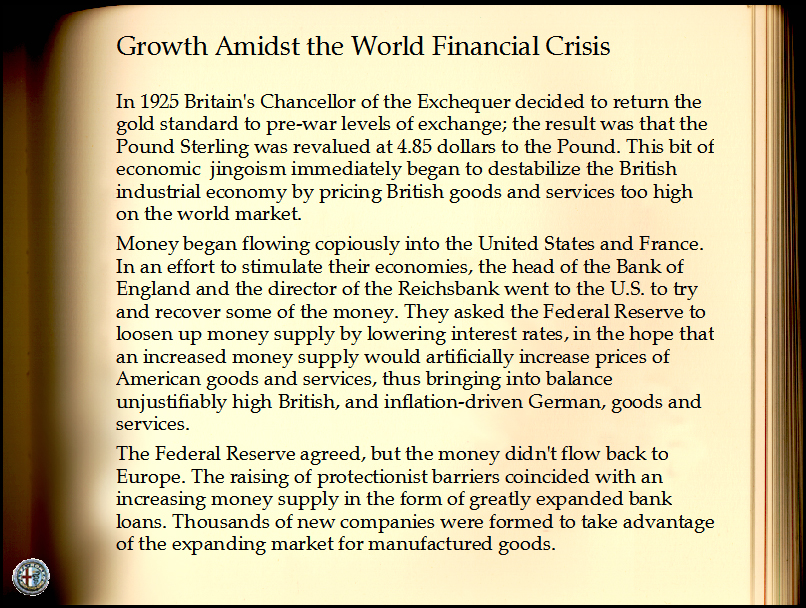

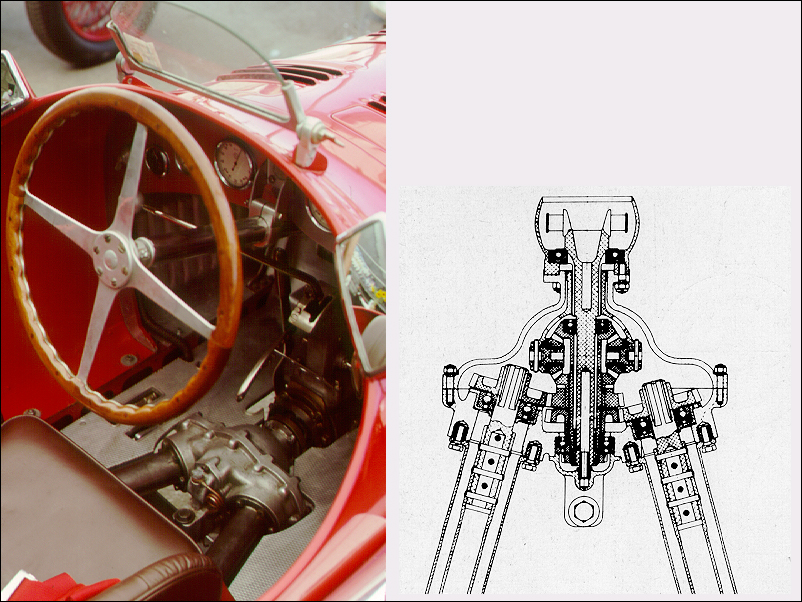

Thus began the three year journey of pioneering what has become e-publishing, and the first digital automotive publication; Alfa Romeo: View from the Mouth of the Dragon. Released in the autumn of 1996 that you see here.

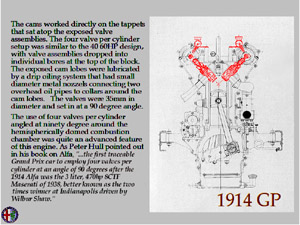

To do this I had to innovate a new form of literature that transformed the traditional linear plot of print and broadcast, into a multi-threaded plot structure, that was navigable yet sequential. Lots of digital animation had to be developed to bring alive the engineering drawings that unfolded at the speed you read the text describing, say, the twin cam 1750 engine of 1929. Then that problem with video had to be addressed for all the archive film of the old 1920 and 30s Grands Prix. It turned out I had actually acquired the film, so I thought screw the video step, let's just take the 24 frame a second progressive image film straight digital. Everyone in the valley said I couldn't do it. Well, I did and the computers' OS loved it. I also thought let's program this at 800 X 600, rather than the prevailing 640 x 480 monitor res of the time.

How did I go from a Mac Classic II replacement for my typewriter to the programming advancements mentioned? Well not because any programmers in the Southern California computer community wanted to help. They saw me as a hopeless neophyte. So I went North. At the dinner introduction with an old main frame programmer, over after dinner brandies, he said, "Well, as TV producer, it's obvious you don't know anything about computers."

With this I began to raise out of my patio chair, it was a beautiful warm evening, and head for the door. I had heard this all before, and was in no mood to hear it again.

Unfazed by my obvious aggravation, he continued, "And that's exactly why we have to do this. Because you think like a TV producer and not a programmer.

"Programmers," he continued, "Just program to impress themselves and other programmers. You'll produce this to be entertaining."

With that, I sat down and formed a close association with Tom Ellis who patiently over the next two and a half years taught me how to program, and in the process, hot rod the primitive digital animation and film programs.

In the end it was best summed up by James Elliot then Managing Editor at Classics and Sports Cars in his September, 1997 review:

"Make no mistake, this hi-tech CD-ROM is actually a book. Alfa Romeo: View from the Mouth of the Dragon comes from the States and traces the history of Alfa from its Darracq roots and through all the great characters such as Ferrari, Jano and Merosi. To use the book you need a PC running Windows and-be warned-it does take a little getting used to reading a book on a computer screen. On the plus side S Scott Callan and Kip Crosby's book is an absorbing read and the big advantages of all this technology are motion sequences and subfiles on the more important figures. An excellent 500-page 'living archive' as fascinating as it is encyclopaedic."

… And for the entertainment of those programmers reading this, we did it all on Windows 3.1. It was so stable it ran on every W95 based OS right through to XP.

There was just one problem with this realization, I had no idea what digital media was.

Yes, I like so many had a new Mac classic II. But it was, for me, little more than a typewriter with an attached filing cabinet, with some great editing features.

I had though, a vague vision of what I had in mind. I had written it on a cocktail napkin the evening before while drinking a good single malt at a pleasant local. The vision was based on what I had been doing for the past two years.

I had saved the first automotive magazine style TV show on the Discovery channel by producing, and financing, four shows from Europe. I say shows, rather than the seven minute segments they aired as, out of respect for the arrangements they took, the miles traveled and the amount of footage shot. I had done it all on a bet. I had spent the last several years in the Italian Motorcycle industry, and had remarked to one of the show's segment producers that the Discovery show needed some real automotive stories of depth and character. Implying this would be a good way to attract a solid viewership and some good automotive industry sponsors. Thus the bet made at the Long Beach GP. Six months later I had a crew in Europe to shoot shows on BMW Motorsport and the M5 cars, the first visit to the new Bugatti factory in Campogalliano and first test drive, Peter Kaus's Rosso Blanco Museum, and the amazing designer Franco Sbarro at his school in Grandson Switzerland, outside Geneva.,

From there I produced arguably the first personality driven automotive show, with Tim Allen, training for and racing in the Long Beach GP Celebrity race for NBC.

From there I had raised the capitol, 75K, for the pilot of a new show. This I chose to do on the relationship between the Italian high performance manufactures and the Carrozzeria. Hell it was a way to get back to Italy and visit Bertone, ItalDesign, Pininfarina, Zagato, Alfa, Ferrari and Lamborghini, and see if they wanted to let me screw up production for a day or two while we filmed. They did.

This then became part of a bigger series in development with Time Warner, with a 350k budget and broadcast guarantee. Now, you'll notice the all important phrase there, 'in development'. Let's just say 'in development' can be an interminable purgatory in TV production. This was not to prove too interminable, as our budget had been reallocated, as did many a production budget 'in development', to develop the hardware and software of the first interactive TV system for TW's Orlando network.

But while we had been in development, Michael Israel, who was TW's creative director, and I had spent some time in TW's newly established digital lab. He was showing me how they were taking videos of comedy stage acts onto this new platform called CD-ROM. Now the problem, as I saw it, was that computer OS hated 29.9 frame per second interlaced video. It seemed to follow the audio track, dropping frames at will to keep up. Kind of like the Jack Benny radio hour with bad visuals.

It was later that evening, over the aforementioned scotch that I had an idea. I was growing weary of the short Cliff's Notes scripting and production of automotive TV. Wouldn't it be interesting to use this new medium to blend the depth of a print publication, with the film, animation and audio of broadcast?

Fortunately this concept, and the inspiration, or perhaps, future vision justification of Miles' getting his info from digital media, came three days before we found out our budget for the new car show was going to Orlando without us.

Thus began the three year journey of pioneering what has become e-publishing, and the first digital automotive publication; Alfa Romeo: View from the Mouth of the Dragon. Released in the autumn of 1996 that you see here.

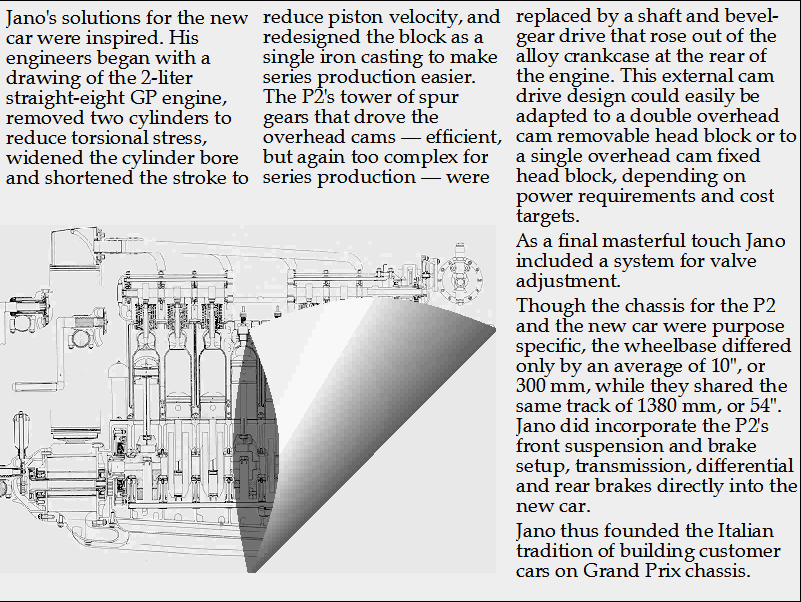

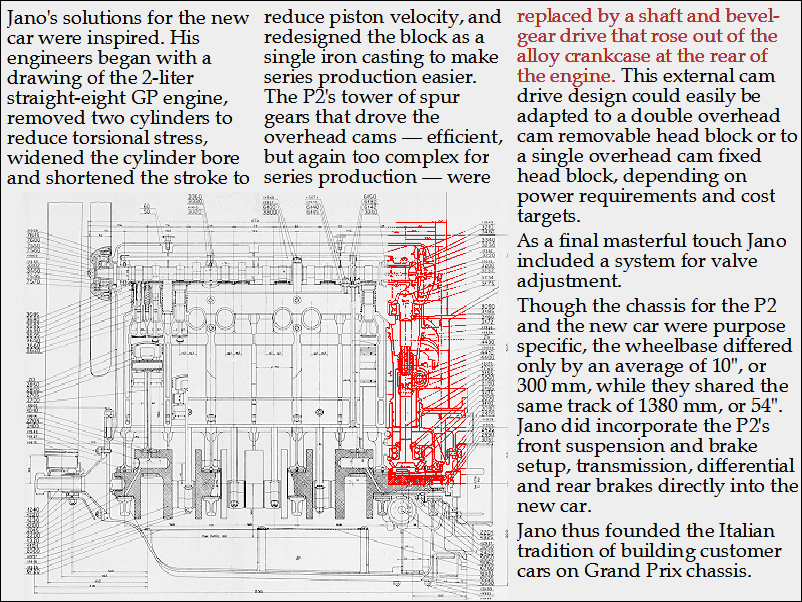

To do this I had to innovate a new form of literature that transformed the traditional linear plot of print and broadcast, into a multi-threaded plot structure, that was navigable yet sequential. Lots of digital animation had to be developed to bring alive the engineering drawings that unfolded at the speed you read the text describing, say, the twin cam 1750 engine of 1929. Then that problem with video had to be addressed for all the archive film of the old 1920 and 30s Grands Prix. It turned out I had actually acquired the film, so I thought screw the video step, let's just take the 24 frame a second progressive image film straight digital. Everyone in the valley said I couldn't do it. Well, I did and the computers' OS loved it. I also thought let's program this at 800 X 600, rather than the prevailing 640 x 480 monitor res of the time.

How did I go from a Mac Classic II replacement for my typewriter to the programming advancements mentioned? Well not because any programmers in the Southern California computer community wanted to help. They saw me as a hopeless neophyte. So I went North. At the dinner introduction with an old main frame programmer, over after dinner brandies, he said, "Well, as TV producer, it's obvious you don't know anything about computers."

With this I began to raise out of my patio chair, it was a beautiful warm evening, and head for the door. I had heard this all before, and was in no mood to hear it again.

Unfazed by my obvious aggravation, he continued, "And that's exactly why we have to do this. Because you think like a TV producer and not a programmer.

"Programmers," he continued, "Just program to impress themselves and other programmers. You'll produce this to be entertaining."

With that, I sat down and formed a close association with Tom Ellis who patiently over the next two and a half years taught me how to program, and in the process, hot rod the primitive digital animation and film programs.

In the end it was best summed up by James Elliot then Managing Editor at Classics and Sports Cars in his September, 1997 review:

"Make no mistake, this hi-tech CD-ROM is actually a book. Alfa Romeo: View from the Mouth of the Dragon comes from the States and traces the history of Alfa from its Darracq roots and through all the great characters such as Ferrari, Jano and Merosi. To use the book you need a PC running Windows and-be warned-it does take a little getting used to reading a book on a computer screen. On the plus side S Scott Callan and Kip Crosby's book is an absorbing read and the big advantages of all this technology are motion sequences and subfiles on the more important figures. An excellent 500-page 'living archive' as fascinating as it is encyclopaedic."

… And for the entertainment of those programmers reading this, we did it all on Windows 3.1. It was so stable it ran on every W95 based OS right through to XP.

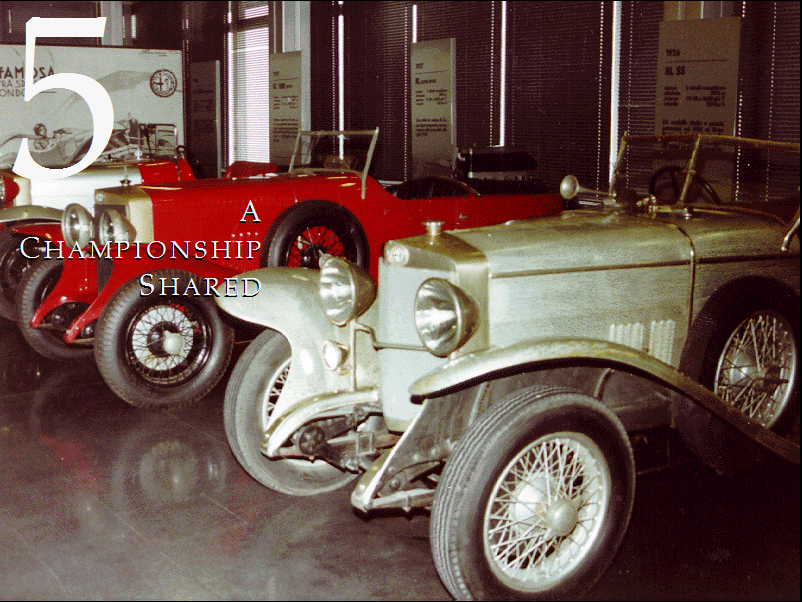

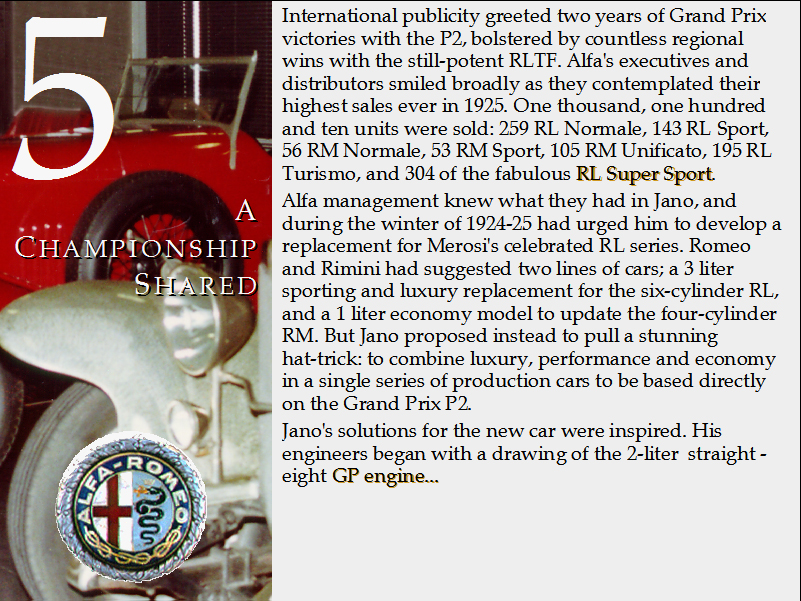

Click images to enlarge

The first automotive digital publication 1996.

the second e-book ever published.

the second e-book ever published.

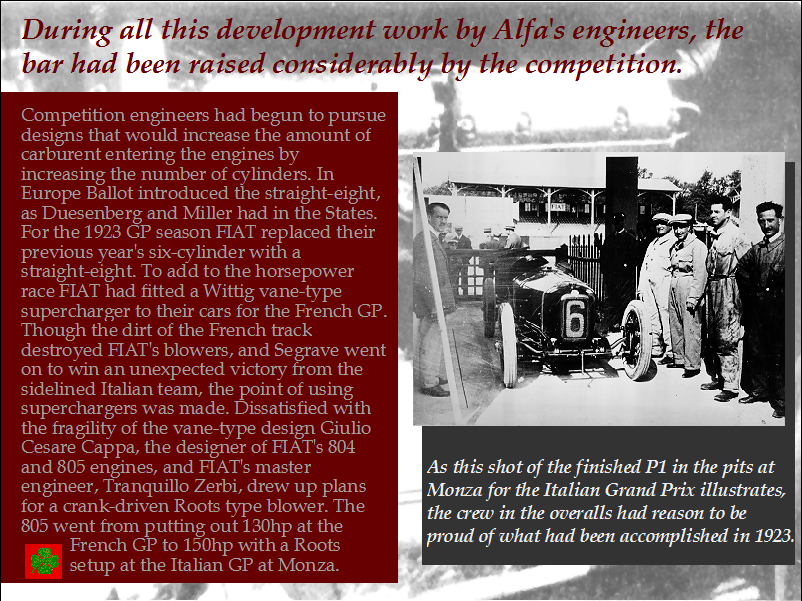

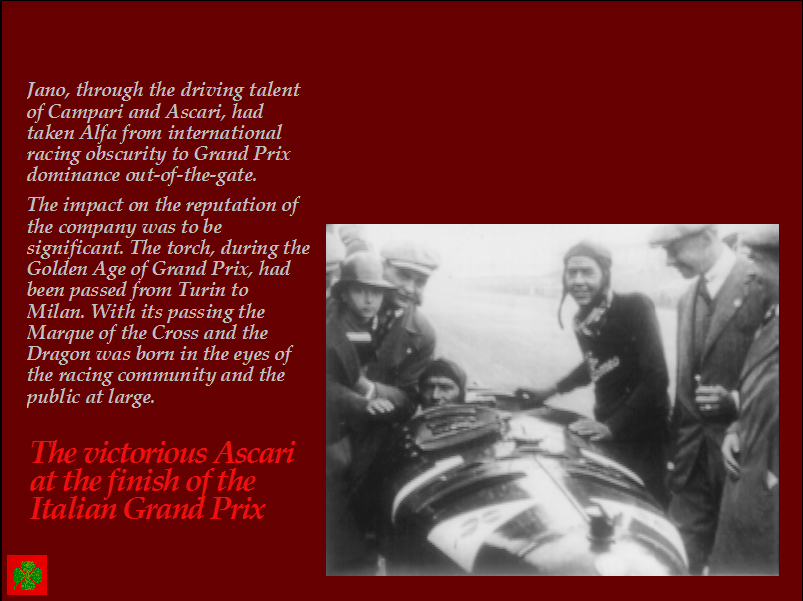

The Autoweek ad photograph...with laurel leaves on old dirt road